Jean Gaumy, Prisoners' horseplay. St Martin de Ré. Prison. France. 1978

Preamble: Jean Gaumy puts the fear of God into me. As an art historian, I am supposed to know how to describe and relate his ouevre. Quite honestly, the thought of discussing his work paralyses me. He embodies almost all attributes I respect in fine artists. What words build on his thoughtful photography?

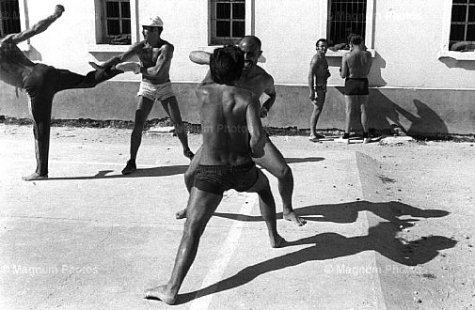

Jean Gaumy. Sports training of prisonners in the walking court. St-Martin-de-Ré. La Citadelle. Prison. 1976

Gaumy’s intellectual curiosity in his subjects – which translates as respect – was an atypical regard for prisoners during the 70s. At that time, he was one of the few photographers paying attention to criminal justice systems. He was the first photojournalist allowed inside French prisons. Les Incarcérés established Gaumy’s reputation as a thoughtful artist who revealed to society its lesser known undertakings.

Sure enough, Danny Lyon was working in Huntsville, Texas in the early 70’s but he was an inheritor of civil rights awareness and his project Conversations with the Dead has always been discussed in political terms first. Perhaps it is an unfair comparison of two great artists working in two different penal systems; perhaps it was easier for Gaumy in France to be neutral and curious. Gaumy operated without the spectre of racism and violence as existed in the South, in Texas and on death row.

Jean Gaumy. Seine-Maritime. Rouen. Prison. France. 1979. Cell-door grating: the old system for serving meals and delivering mail to convicts.

The impression that Gaumy actually cares for his subjects may be a confusion with the possibility he just understood them. A great many of his pictures are so unique (and one presumes a long-time-making) it can be said without doubt he knew his subjects. They knew him well enough to either ignore the camera or look directly at it to communicate clear messages. Let me explain: when a camera first enters an environment it steals the attention and comfort of most subjects. At this point a great many images are of subjects reacting directly to the camera’s novel presence, and of subjects calculating the nature of their relationship to the camera and operator. For this to pass the camera must be around long enough for it to ‘become invisible’. Thereafter, when the subject addresses the camera directly, it is purposeful – with a message – a not as a reflex reaction.

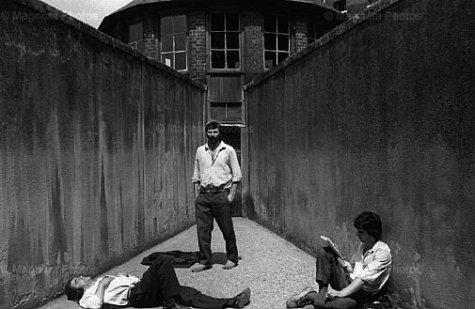

Jean Gaumy, Maison d'arrêt. Caen, France, 1976. Surveillance in the Passageway.

His work is that which enriches the viewer the longer they spend with it. These are not platitudes. Over the course of several years, with craftsmanlike rigour and repeated visits to many institutions, Gaumy pieced together a body of work (ultimately for his 1983 book, Les Incarcérés) that held a mirror to the multitude of attitudes and realities of prison life.

Jean Gaumy. Convict in his Cell, St-Martin-de-Ré. La Citadelle. Prison. 1976

Rather than taking a position or preferring the stories of one group over another Gaumy flits about the different prisons and – through (as I suspect) thorough editing – presents prisons as predictable places that are occasionally enlivened by quirks of human behaviour. Gaumy’s photography shows the machismo of a minority of inmates only after it has shown the solitude of some, the collective boredom of others, the routine awareness of guards and the bureaucratic tasks of the prison itself. There are no stereotypes in Gaumy’s work, and there a very few visual clichés.

Jean Gaumy, St-Martin-de-Ré. Prison. La Citadelle. France. 1976. Administrative procedure for the release of a prisoner.

Gaumy’s craft is the manner in which he casts an even hand over all objects and subjects. His studies of guards at their most relaxed and animated are as interesting as that of the lounging inmate reading his paper (as if a photographer stands in his cell every day). Well perhaps Gaumy did stand in his cell every day … for a period. Such is the familiarity of Gaumy’s portraits some could be mistaken for subjects in their own houses. Now is this Gaumy’s fabrication, or were the institutions of St. Martin-de-Ré; Maison d’arrêt, Caen; Seine-Maritime, Rouen; Ile-de-France, Seine-et-Marne, Melun; and the Calvados, Basse Normandie really as calm as he depicts? There is no violence, barely even tension among the inmate or guard populations.

Jean Gaumy. Transit lock chamber between the walking courts and the cells. St-Martin-de-Ré. Prison. La Citadelle. 1976

Jean Gaumy. Tattooed Prisoner. 1978. Charente Maritime region. Poitou Charentes department. Village of Saint Martin de Ré. La Citadelle. Prison. Saint-Martin de Ré was the departure point for prisoners who were sent to the Cayenne prison in French Guyana. The last shipment of convicts was in 1938.

The only suggestions of violence power Gaumy portrays are the immediate exertions of the weightlifter and, alternatively, the viewers semantically-derived understanding of violence as exhibited in tattoos.

Gaumy makes four individual studies of tattoos. It is hard to comprehend whether Gaumy was original in this. Today we are saturated with images of the tattoo, to the extent that street graffiti, body art and gallery hangings are one and the same; not a year passes without a photojournalist embedding themselves among gangs (either within or without prison) to study the pervasiveness of ink and brevity. Maybe I am biased, but I like to think of Gaumy’s interest in the tattoos of social transgressors, as an artist pioneering a genre in its infancy.

Jean Gaumy. Sports training of prisonners in the walking court. City of Caen. Prison. 1976.

Jean Gaumy. Coming on watch of warders' team. Ile-de-France. Seine-et-Marne. Melun. Prison. 1978

Gaumy kept adding the layers. Unwilling to present only the palatable human side – and seemingly unable to present the darker side of prison life – Gaumy changed his viewpoint. At times his lens was that of a fine artist concerned with shadow and form, at others his eye was that of a faux-Precisionist prompted by the reductive lines of prison architecture. Only Gaumy’s work differed from Charles Sheeler’s et al because of the presence of people – ants; dots; inhabitants. Gaumy’s work, inclusive of crowds, repeats the affections of Lowry. Gaumy’s act of recording is a testament to the physical imprisonment of these French men as Lowry’s was a testament to the social imprisonment of Salford’s working class.

A Street Scene in Clitheroe, L.S. Lowry.

As I write, another (probably meaningless) similarity between the two men springs to mind. Lowry was always drawn to the sea, particularly England’s Northeast coast and the North Sea. He returned to it into his old age. Gaumy late in his career has grappled with the enormity of the oceans. I could hypothesise both artist’s careful handling of mankind derives from an ever-present haunting of that which is larger than mankind. To appreciate the awesome scale of the sea is to wonder at the fragility of man. Ask a surfer … or a fisherman.

Gaumy also manages to reconcile – If one presumes them at opposite ends of the same spectrum – the human scale and the systemic scale of prisons. Couldn’t the three pictures below be by that of a different hand, and yet don’t they make perfect sense grouped together?

Jean Gaumy. "Bonne Nouvelle" prison ("Good news" prison). 2nd section. Walking court. Seine-Maritime. Rouen. Prison. 1979

Jean Gaumy. Walking Courts, Caen. Maison d'arrêt. 1976

Jean Gaumy. "Bonne Nouvelle" prison ("Good news" prison). 2nd section. Walking court. Seine-Maritime. Rouen. Prison. 1979

Gaumy got close in and later retreated right back. Even if this is considered a privilege of a photographer with free passage through the walls of a prison, it does not guarantee good execution. My favourite image is the church service attended by a congregation of boxed men. Gaumy lays bare the crude and incongruous use of discipline and religion, and in doing mocks the scene. The viewer can’t fail but be in agreement with Gaumy; the interaction is absurd and directly contradicts the extraordinary ordinariness of Gaumy’s other scenes.

Jean Gaumy Mass in the chapel. The prisoners are isolated in individual compartments. Caen. Maison d'arrêt. 1976

Gaumy, it seems, didn’t want to extricate himself from the action, nor from the space and time spent on the series. Unwilling to let himself nor the craft of photography off the hook, Gaumy includes three studies of the anthropometric photography room. This is not a Surrealist maneouver, but it does point toward the Postmodernist insistence that the practitioner is an inevitable part of the work. Gaumy never intended to be an objective viewer but rather an active participant (he only ever took photographs with the prisoners consent) and the images below are an open admission of photography’s classifying, even disciplining, function. The camera … the metre-rule … the artificial light … the document … the knowledge … the authority.

Jean Gaumy. Anthropometric photography of a convict at his arrival in prison. Basse Normandie. Calvados. Caen. Prison. 1976

Jean Gaumy. Anthropometric photography of a convict at his arrival in prison. Basse Normandie. Calvados. Caen. Prison. 1976

Without doubt, Gaumy was fortunate to have a wild-haired caricature sitting for this particular anthropometric observation. The docile subject is the perfect compliment to the act of observation and documentation. The treatment of this prisoner is akin to expedition-photography that attempted to measure the anatomical dimensions of colonised peoples and thus provide scientific evidence for Western genetic superiority. This appreciation is the perfect close to a series throughout which Gaumy balances his artistic aims, social purpose, photography’s interferences and the loaded history of Modern taxonomic praxis. Gaumy dismantles assumed norms and hierarchies of social order and allows the viewer to meditate on the subtleties of carceral systems.

I escaped my paralysis, jolted by the news that last week Jean Gaumy was awarded the Peintre de la Marine (Painter of the Fleet) by the French Ministry of Defence. Gaumy is only the fifth photographer to join the select circle, which is composed of only 40 members.

For a full biography and portfolio please visit the pages of Magnum Photo Agency.

The folkology (keyword tags) within the Magnum archive are inconsistent. Different sets of Gaumy’s images turn up for different searches. Here is another isolated set for St-Martin-de-Ré. La Citadelle also from 1976. I would encourage readers to search at length Gaumy’s work throughout the different institutions with permutations on keyword searches.

3 comments

Comments feed for this article

March 31, 2010 at 8:14 am

POSI+TIVE MAGAZINE > Reportage > Prison Photography

[…] am also proud of my analyses of Jean Gaumy Cornell Capa Jane Evelyn Atwood Jenn Ackerman and Patricia […]

April 18, 2014 at 1:02 am

Birds Lift Lieven Nollet’s Disquieting View of Belgian Prisons | Prison Photography

[…] the sake of positioning the work, I’d say it has elements of Jean Gaumy‘s tight European jail photographs, the spiritual element of Danilo Murru‘s photographs […]

April 29, 2015 at 1:31 pm

That One Time Photographer Grégoire Korganow Was Made an Inspector of Prisons in France | Prison Photography

[…] Korganow has made the most of his phenomenal access producing an unrivaled and varied of body of work about the French prisons. Nothing as engaging has emerged since Mohamed Bourouissa’s Temps Mort, Mathieu Pernot, Les Hurleurs, and (going way back) Jean Gaumy’s Les Incarcérés. […]